Plant-based Architecture and Living Facades: The Intersection of Biology and the Building Skin

A question for architects and the building industry: Can our cities be part of the solution to the challenges facing humanity, or are they intrinsically and inevitably a big part of the problem? To move beyond the latter demands nothing less than a fundamental shift in the way we think about buildings. Let’s pull on this thread for a minute.

Dream with me! Reality has become rather furcated and ambiguous these days anyway, so I invite you to join me in a little mind-game here, a meditative exercise in what could be. Imagining creates the potential for manifestation; if we can imagine it we can realize it, if we can’t imagine it, well, forget about it. So, for a moment, instead of dwelling on how dreadful things have been lately, let’s indulge ourselves in imagining how good they could be. I’m talking about urban habitat, by the way; a vision of how absolutely lovely our cities could be. I’ll start, but you can carry on along your own trajectory to see where it takes you. (Close your eyes and run with it; what do you see?)

I see garden cities. Paved streets are gone, replaced with tree-lined parkways and pedestrian walkways that meander through the city, integrated at neighborhood nodes with outdoor cafes, restaurants, food vendors, farmer’s markets—featuring produce from the neighboring urban farms—and tiered gardens of veg and flowers. Birdsong is everywhere. Mushrooms bloom, ferns and mosses grow in the fertile understory of the leaf canopy and the rich smell of humus conjures the feel of deep forest. Small wildlife thrives. I pass a robust young chestnut tree. (In another 600 years it will be named and famous and with multiple honors and awards, a tree worshipped by the people of the future.) Pollinators in abundance are busy in the native plant gardens. The bumble bee, monarch, and other small animal populations are booming.

Lift your gaze upward and the sprawling greenery extends from the ground plane. Hard structure is difficult to see cloaked amidst terraced walls and cascades of variegated plant forms. Solar glare and the noise of a busy metropolis are swallowed in foliage. The air is sweet and clear, filtered through the multi-layered leaf and plant canopy. The plunging biodiversity and feared sixth mass extinction event have been reversed; the wildlife is so intense and concentrated that scientists have been busy tracking the emergence of new species of flora and fauna.

Okay, enough already, you get the picture. So, where do facade geeks play into this vision? I’ve been spending a lot of time in the garden these days. I realized a while back that building soil, growing veg and pollinator plants, and building local biodiversity was probably the biggest contribution I could be making to carbon reduction and the pursuit of shared resilience and sustainability goals. I became especially interested in emergent findings and developments in soil science, which are slowly revolutionizing the practice of agriculture (if you haven’t already, see Kiss the Ground for a much needed dose of inspiration). Healthy, living soil rich in microbial life can sequester enormous amounts of carbon without the decades-long lag it takes for trees to mature into efficient sequestration vessels.

So I’ve been getting dirty. When I’m out there with my hands in the dirt, when the earth has sucked all the tension and anxiety out of me, I wonder about the intersection of facade systems and biology; biofacades, if you will. We know of the relevance of the facade system with its linkages to virtually everything in buildings and urban habitat, and its potential as the fulcrum of integration bringing all of these disparate elements into an optimally efficient, harmonious balance. We recognize that the realization of that potential in urban environments, dominated by mid and high rise buildings, necessitates the activation of the facade system; improving the performance of buildings and urban habitat is all about enhancing the behavior and functionality of the facade system.

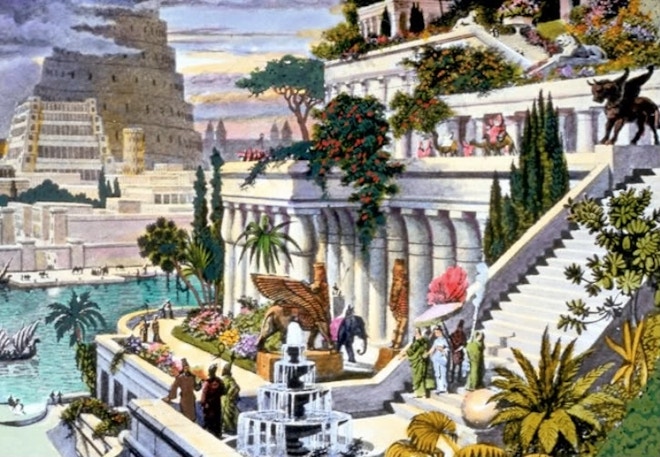

Figure 1: 19th century engraving depicting the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon, thought to have been constructed approx. 600 BCE.

The biofacade concept is not new. Historical roots track back to Hellenic culture and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (fig.1), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Visionaries like Glen Small (link to feature) and recent pioneers like Ken Yeang (link to feature) and others have been exploring this notion for decades. Most built work pursuing this concept has taken the form of green roofs and walls. More recently, interest has grown in the integration of microalgae systems in the building facade, spurred by the first such application—the Solar Leaf—in Hamburg by Arup in 2013. But even the ambitious, recently completed 1000 Trees project (fig.2) by Heatherwick is modest in comparison to our shared vision of what could be. So, while the biofacade concept is not new, it does represent a new and largely unexplored modern frontier for research and practice in the building arts and sciences, one with great promise for beautifying our cities, improving the resilience and sustainability of the built environment, and enhancing the quality of life for billions of urban dwellers—the UN projects that nearly 70% of the projected global population of 9 billion will live in major urban areas by 2050.

Figure 2: The 1000 Trees project, 2018, Heatherwick, under construction in Shanghai. (Image courtesy of MNXANL; cropped)

And the intersection is not just the crossroads of facade and biological systems. It’s a crowded interchange that also includes whole building design and delivery, indoor air quality, landscape architecture, urban planning, health and wellness, biophilia, and other important aspects of the biological, ecological, and social sciences. Healthy ecologies are literally rooted in and spring from living, healthy, microbial-dense soil. How can we optimize the facade zones of urban buildings to host the robust soil microbiomes required for thriving facade ecologies? Forget the decorative landscaping at the ground plane, we want buildings layered in facades teeming with native and climate-appropriate plant and small animal life.

It’s not a vision of a building with a veneer of green or a building that incorporates a farm or a forest. It’s a building that is a farm and a forest that also happens to incorporate some level of commerce and human habitat. It’s a building that nurtures biodiversity, a facade zone where species evolution can be tracked, where nature filters sound, fresh air, and sunlight, where phenomena like the vertical migration behaviors of various pollinator species can be researched…

A Living Building!

This issue leads with an original article on biofacades for SKINS by authors Mary Beth Bonham (author of the recent book Bioclimatic Double Skin Facades) and Kyoung Hee Kim (author of the recent book Microalgae Building Enclosures: Design and Engineering Principles). They effectively shape the context for the rest of the features in this issue and, more importantly, for a broader industry discussion about moving beyond surface considerations of green walls, roofs, buildings, and into a deeper integration of building and biology. Big thanks to Mary Ben and Kyoung Hee for this important contribution.

The question posed by John Cumbers writing in Forbes follows from the consideration of living systems: “Can we grow our buildings” [and facade systems]? A leading edge of the building industry has been considering this, in various forms, for some time. Cumbers explores some of this work and discusses the potential benefits that living buildings might provide. One of the people he quotes is Rachel Armstrong, a professor of experimental architecture (cool!) at Newcastle University, who doesn’t think much of current building practices, labeling them as Victorian era technology. Our third feature links to a TED talk she did at Future Tech Week. (For more on microbiomes in buildings, check out this article in The Conversation.)

Materials and material explorations are invariably integral to emergent technology, and the realm of the building/biology interface is certainly no exception. Academics and practitioners both have been exploring biomaterials. In this issue we include a Dezeen piece that investigates developments in biomaterials, a prototype living facade developed for the Architectural Ceramic Assemblies Workshop (ACAW), and a look at mushroom architecture.

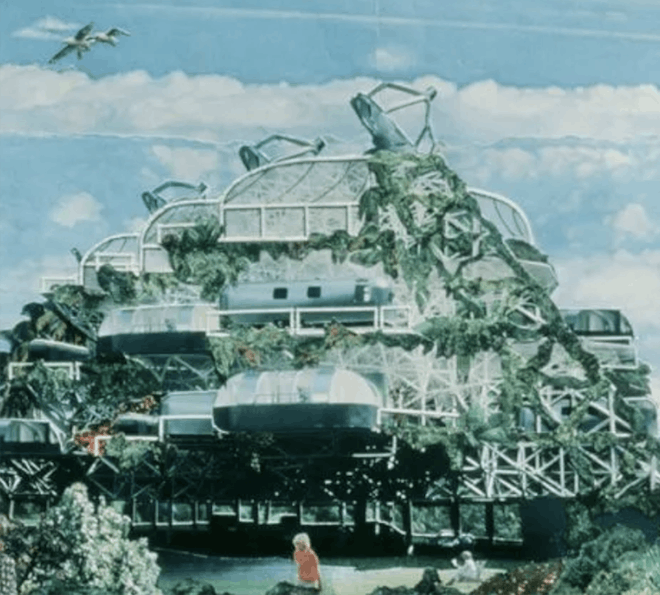

As we like to do in SKINS, we next introduce two seminal figures in the green architecture movement, Glen Small and Ken Yeang, neither widely known and both regarded (at least by some, me included) as unsung heroes in the field of architecture. I first met Glen in 1980 on Venice Boulevard in LA where he was exhibiting his conceptual Green Machine (fig. 3). Ken has published an impressive number of books and papers that are well worth a read, and much has been written about his work.

Figure 3: Rendering of the conceptual Green Machine, Glen Small, 1980. (image from the architect’s website)

We finish with a few items of note, including a new graduate facades certificate program at USC, a journal call for abstracts with a deadline coming up fast (end-of-month), and a newly published book, Rethinking Building Skins. It’s well past time for that!

We all hope you enjoy the issue and shower us with praise, but we’d love to hear your criticisms too, along with your ideas on what you would like to see in future issues of SKINS.

Please keep the (bio) dialogue going!

Best regards to all,

Mic Patterson

Great thanks from all of us at

The SKINS Team:

Mic Patterson, Facade Tectonics Institute

Executive Editor

Val Block, Facade Tectonics Institute

Associate Editor

Brienna Rust, SGH

Christopher Payne, Gensler

Content Editors

Alberto Alarcon, Kuraray

Event Calendar Editor

If you would like to join the SKINS team, let us know at skins@facadetectonics.org. There is much to do!

Mic Patterson, PhD LEED AP+

Ambassador of Innovation & Collaboration

Facade Tectonics Institute

Looking for something specific?

Search our extensive library.

FTI’s SKINS email is the central source for the latest in building skin trends and research.

All emails include an unsubscribe link. You may opt out at any time. See our privacy policy.