Facade Futures: Building Resilience is Skin Deep

There is currently a natural tension arising between the need to engage climate change mitigation versus adaptation. Clearly, we need to reduce our current carbon footprint drastically in the short term to avoid global warming tipping points and the associated severity of climate change we are already witnessing today. But it is unclear as to the most prudent strategy for minimizing damages and disruptions due to extreme weather events that will challenge the resilience of our built environment. For the built environment, in particular buildings, the question is: do we focus on reducing the carbon footprint of new and existing buildings, or do we look at enhancing their resilience? Can we somehow do both?

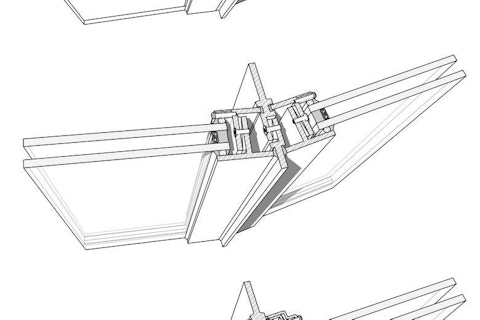

Climate change and extreme weather events have placed a renewed interest on resilience, and in particular the resilience of enclosures, since they represent the most significant passive system separating the indoors from the outdoors. Unlike HVAC systems, façades keep working during power outages to provide shelter and enable survival. If the same importance was placed on the design of façades as the structures of our buildings, then resilience would not be an option but a minimum requirement based on limit states design principles and future climate. Building enclosures would have to provide a minimum level of passive habitability under both hot and cold periods of extended extreme weather events coinciding with prolonged power outages. The facade would also have to be able to resist damage from flooding, windborne projectiles, and in certain regions provide protection against wildfires.

While building codes are slow to change and focus predominantly on minimum levels of health and safety from fire and structural collapse, the increasing severity of extreme weather events induced by climate change are beginning to adversely impact human health and safety. If codes and standards do not evolve, the insurance industry will impose premiums that reflect the damages and losses in buildings resulting from climate change, and in some cases assets may not be insured altogether because the risks are too high. Either way façade design will have to address the need for enhanced resilience. But can this higher level of performance be achieved within a sustainable carbon footprint? When answering this question it is important to appreciate that resilience is not the new sustainability, and while the two concepts are related, they should not be confused.

The Difference Between Resilience and Sustainability

Resilience, like sustainability, will not go out of style. These two performance objectives are related to one another, with sustainability being a broader and longer-term process that periodically hinges on our ability to be resilient and bounce back from adversity so that the sustainability agenda is not set back and further compromised.

Resilience is a complex attribute that is comprised of numerous aspects - some physical, some technical and some social and cultural. We become aware of resilience when it is absent or insufficient and we are unable to persevere and overcome challenges such as extreme weather events. It is also important to imagine how a facility will continue to serve its constituency during a pandemic where physical distancing and ventilation become critical factors to enable the ongoing viability of sheltering. Façades moderate the environment but they are also key to natural ventilation of spaces when mechanical ventilation system are disabled during power outages. However, façades cannot be the only line of defense yet robust resilience is practically impossible when façades represent the weakest link.

re·sil·ience

1. the act of rebounding or springing back;

2. the capacity to adapt to changing conditions and to maintain or regain functionality and vitality in the face of stress or disturbance.

Sustainability is not possible without resilience, but to describe the relationship between these two concepts in the vernacular of mathematics, resilience is a necessary but insufficient condition for sustainability. Resilience is like a shock absorber that allows for a safe, smooth ride while sustainability is the road taken – one that hopefully does not lead to a precipice or dead end.

Facade Design for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Climate change mitigation demands that we lower both the operating and embodied carbon of buildings. Decarbonization of our building stock requires the electrification of HVAC systems that are currently powered by fossil fuels. In order for heat pump technology to be cost effective and the electrification not to strain peak load demands on the grid, the facade must provide a high level of thermal control. For existing buildings a deep retrofit will typically include an overcladding solution for the building façade that needs to be low in embodied carbon and sufficiently durable to realize the life cycle savings needed to ensure cost effectiveness of the investment. And it must provide adequate resilience to avoid the high costs associated with potential damage of the façade during extreme weather events. The same goes for new buildings except there is greater design flexibility in the façade design because it is not tied to an existing structure and façade system. It is also important to appreciate that for new buildings high-performance façades permit the deployment of low intensity heating and cooling systems that in turn require smaller piping and ductwork, incur less embodied carbon and lower HVAC system costs. So what used to be a tradeoff between higher HVAC system efficiency for a less efficient enclosure can now be reversed with the HVAC system savings being leveraged to offset the cost of a high-performance façade. And instead of compromising resilience it is being significantly enhanced.

What are the practical limits that need to be imposed on window-to-wall ratios in various climate zones? How do we adequately protect against glass breakage from wind-borne projectiles? Are punched windows inherently more resilient than window-walls and curtainwalls? There are many questions that need to be answered before embarking on the research and development of appropriate technological solutions. We do know that there is no one-size-fits-all solution and so we will have to consider climate, frequency and severity of extreme weather, building use and occupancy, and then strike a balance between risks and consequences. There is no reason that resilience cannot become as sophisticated and cost effective as the seismic design of building structures.

Buildings involve a lot of materials, components and systems that need to work together and so gaining a broader perspective of the resilience challenge enables us to work with our allied disciplines to better harmonize resilience across the built environment. It's a matter of survival.

Can we design, fabricate, install, commission and maintain low carbon façades that mitigate against climate change but also promote adaptation though enhanced resilience? The simple truth is that we do not have a choice. Fortunately, façade technologies are available for both existing and new buildings that can effectively address both mitigation and adaptation imperatives, but currently there is not a lot of choice and variety of tectonic expression available. The challenge for our facade industry is to stay ahead of government regulation and insurance industry risk aversion by advancing the science of durable and resilient low carbon facades while still affording a high degree of freedom for creative design expression.

It is important to realize that all these topics and issues are related today because both climate change mitigation and adaptation are now widely recognized as essential aspects of our sustainability agenda. As we witness the devastation of extreme weather events and their impact on human lives, our communities and our economy, it is understandable why the average person is looking to our building industry to help find affordable solutions to protect the integrity of our buildings so that they can better shelter us all. Buildings involve a lot of materials, components and systems that need to work together and so gaining a broader perspective of the resilience challenge enables us to work with our allied disciplines to better harmonize resilience across the built environment. It's a matter of survival.

Ted Kesik

Ph.D., P.Eng.

University of Toronto

Looking for something specific?

Search our extensive library.

FTI’s SKINS email is the central source for the latest in building skin trends and research.

All emails include an unsubscribe link. You may opt out at any time. See our privacy policy.